Introduction

Recently Real Biathlon posted data about World Cup Prize Money in biathlon on his website for Patreon members. Combined with all the other data sources he provides, if you like working with data and biathlon why not look into becoming a member as well and support him in keeping the site running? For the Prize Money data, you can easily find the major all-time earners, sort by gender and year, and use the data combined with other data sources he provides.

In the post below I have tried to look at the data from the less obvious perspectives, and see if we can get some interesting stories out of it.

Data source

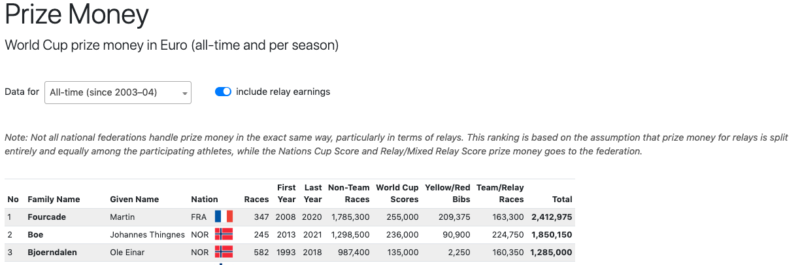

The data contains all income from the IBU at the World Cup level, and excludes any income made from external sources like sponsorships, bonuses from national federations, etc. the data range starts with the 2003-2004 season and it should be kept in mind that some athletes were already active before this season so that data is not included. For team races, the data is based on the assumption that prize money is split entirely and equally among the participating athletes.

The Prize Money data source is in Euros as that’s the currency used in the IBU season guides, the source of this data for most (or all) seasons.

Equality

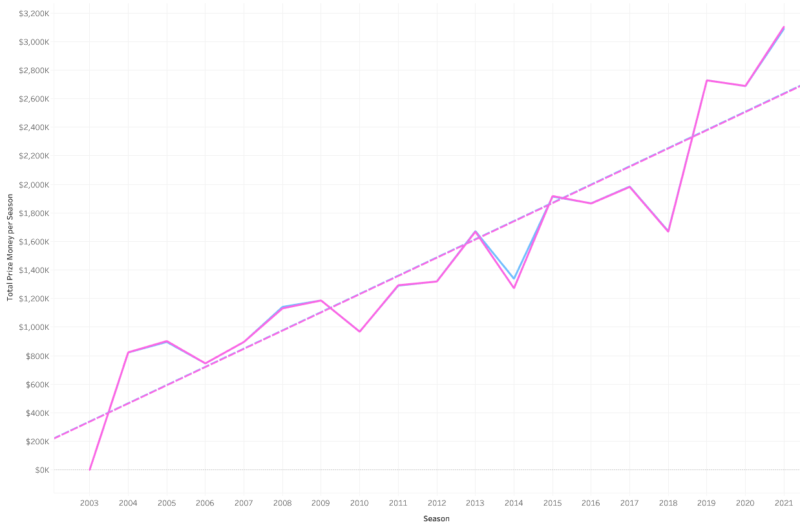

The first thing I wanted to explore is how the IBU deals with equality. And it’s fairly simple: prize money is based on race results, world cup scores, and bibs. And it is unrelated to the gender of the athlete; in other words, the prize money is equally handed out between man and women.

The small changes are likely happening as in some races more athletes get prize money, which then adds up for the season (say three athletes don’t finish a mass-start, the prize money is not handed out). The 2014 season seems to be the only year with a bigger difference, and quite frankly I don’t know why that is. But generally, we can see the pink line for the women pretty much overlaps the men’s blue line.

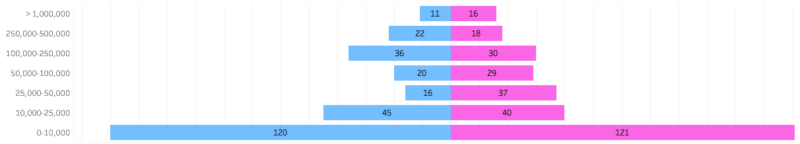

How is the money divided?

If we look at how the prize money is divided, we see that the majority of athletes do not make a lot from their sport (strictly looking at prize money). Of the 561 athletes in this dataset, only 27 (4.8%) have made over a million where 241 made €10,000 or less. And 428 athletes (76%) have made €100K or less since 2003-2004. It also appears the men are a bit more top-heavy with 26% making €100,000 or more, which is only 22% for the women.

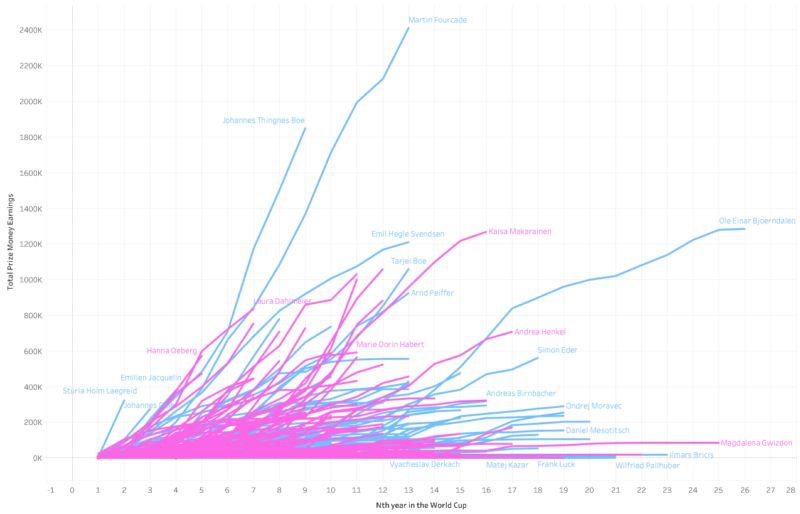

Earning pace

I was curious to see how athletes compared when looking at how much they earned in their first, second, etc. year in the World Cup. I should remind you that if athletes were already active before the 2003-2004 season, their total earnings do not include the seasons before that.

We can see a number of interesting things here, for example that Bjoerndalen didn’t make money until his 12th season (due to the above-mentioned limit in available data), Martin Fourcade made the most in total but could be caught up with by JT Boe, and Jacquelin, Dale and Laegreid are also on pace to get to Fourcades total faster or go above it. Hanna Oeberg and Denise Herrmann are on track for the women to become the biggest prize money earners, although Herrmann started later in her career with biathlon.

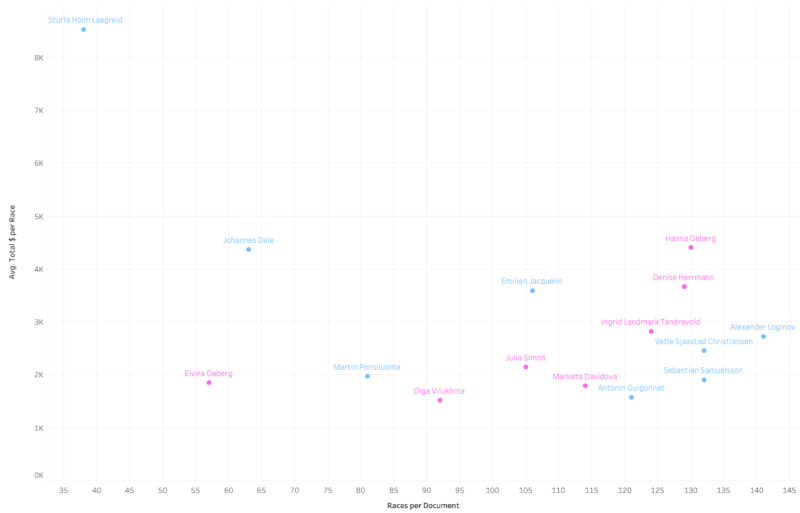

Another way to look at this data is average money made per race. I filtered the chart to only show those athletes that have between 30 and 150 races (to highlight the “new kids on the block”) and have a average of at least €1,500 per race:

After Laegreid’s amazing first full season, it is no surprise to see him high up in the top-left corner. Dale, Jacquelin and Ponsiluoma are also in a strong position to make good money in the upcoming years if they can keep their rates going. For the women, Hanna and Elvira Oeberg, Herrmann, Tandrevold, Simon, Vilukhina and Davidova also have great ratios up to this point in their careers.

Riding the good team train

The last thing I wanted to look at are athletes that have made good money in Team races, but not so much in individual races. In other words, who has been riding the good-team train?

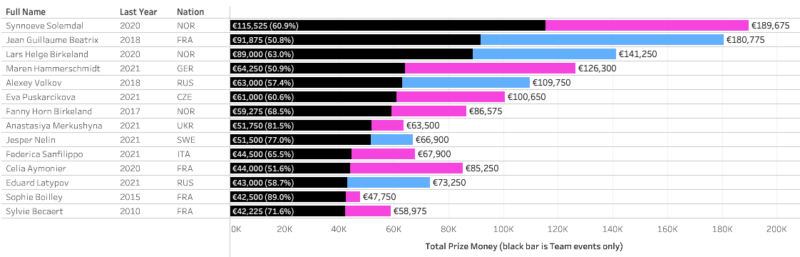

The chart below shows all athletes and their total prize money for team/relay races, and the percentage of earnings for team/relay races compared to their total earnings. To highlight the “train riders” (filled in circles) I selected those athletes who made more money with team/relay events than other ways (team/relay earnings > 50%) and who made more than €40,000 on team races:

Below are the highlighted athletes with more details. We can see that an athlete like Merkushyna made 81.5% of her earnings through team/relay events for a total of €51,750. Given that she has not made much money in individual races, I think she is one of the athletes who most benefitted from being on a good team. Sophie Bailley is another great example.

This Prize Money dataset is a great addition to the site, with plenty of interesting stories to tell!